What is the Paris Agreement?

At COP 21 in Paris, on 12 December 2015, Parties to the United Nations Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) reached a landmark agreement to combat climate change and to accelerate and intensify the actions and investments needed for a sustainable low carbon future. The Paris Agreement builds upon the UNFCCC and – for the first time – brings all nations into a common cause to undertake take ambitious efforts to combat climate change and adapt to its effects, with enhanced support to assist developing countries to do so. As such, it charts a new course in the global climate effort.

The Paris Agreement’s central aim is to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by keeping a global temperature rise this century well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Significantly, the Paris Agreement also placed climate action in the context of efforts to achieve sustainable development, stressing the relationship between climate action and poverty eradication.

Overview of the content of the Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement is 31 pages long with 16 introductory clauses and 29 operative clauses. Expectations in the Paris Agreement are high. According to former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, the Paris Agreement ‘is a monumental triumph for people and planet. […] It sets the stage for progress in ending poverty, strengthening peace and ensuring a life of dignity and opportunity for all’ (Ki-moon 2015).

By charting a new political course for global climate change action it provides the first real hope that we might be able to address climate change in a more timeous, responsible, united, equitable and sustainable way. What sets COP21 apart from previous COPs is that the significance of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities has radically changed. Although Common But Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities maintains its importance as a guiding principle of the Paris Agreement, the strict binary interpretation of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities along the lines of Annex I and non-Annex I parties has been replaced by a nuanced form of differentiation between developed and developing countries, which recognizes that everyone needs to act according to their respective capabilities and resources to tackle climate change.

Some of the key Articles of the PA are outlined and briefly described below:

Article 2: This article reaffirms the primary objective of holding ‘the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and to pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels’. The 1.5 °C objective in particular is a much stronger outcome than anticipated although the difficulty of reaching this target is evident from calculations provided by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the United Nations Environment Program. The 1.5 °C target can be seen as a success of the Small Islands Developing States (SIDS) and Alliance of Small States (AOSIS) in putting forward the scientific argument, in getting powerful developed countries on board and in framing their domestic mitigation activities according to the 1.5 °C target. Article 2 also reaffirms the CBDR-RC principle by stating that the Agreement will be implemented to reflect equity as well as the CBDR-RC principle. What sets the Paris Agreement apart is the inclusion of the clause ‘in light of different national circumstances’, which was first explicitly referred to in the Lima Call for Climate Action in 2014. Arguably, the PA does not provide guidance on the operationalization of equity. However, another interpretation of this paragraph, taking Article 4 into account which states that ‘each party’s successive nationally determined contribution will represent a progression beyond the Party’s then current national determined contribution and reflect its highest possible ambition, reflecting the CBDR-RC principle’, suggests that it forms the basis for a strong obligation for each party to take more ambitious actions over time.

Article 4: This article states the long-term objective ‘to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century’. Given the global warming ceiling specified in Article 2, most scientists interpret this to mean that global net carbon emissions need to reach zero by 2060–2080 (Clémençon 2016). This also implies that beyond the achievement of Net Zero Carbon (NZC) emissions, carbon needs to be actively removed from the atmosphere. The article also states that all countries should ‘strive to formulate and communicate long-term low greenhouse gas emission development strategies’. In combination with binding updates every 5 years, this implies that collective ambitions will be ratcheted up over time as each successive step needs to be at least as strong as the current one. This implies that parties have to submit new or renewed pledges for 2020 9–12 months before the 2020 COP meeting.

Article 6: This article is the most significant innovation in international climate negotiations. Interpreted by many as the Article for carbon markets, it encompasses a much wider perspective by providing the framework for implementation of new, experimental forms of climate governance. Voluntary cooperation/Market- and non-market-based approaches – The Paris Agreement recognizes the possibility of voluntary cooperation among Parties to allow for higher ambition and sets out principles – including environmental integrity, transparency and robust accounting – for any cooperation that involves internationally transferal of mitigation outcomes. It establishes a mechanism to contribute to the mitigation of GHG emissions and support sustainable development, and defines a framework for non-market approaches to sustainable development.

Article 7: This article points towards the desire to establish a global goal on ‘enhancing adaptive capacity, strengthening resilience and reducing vulnerability to climate change’. It stresses the differentiated focus of developing countries on adaptation as opposed to the developed countries’ focus on mitigation while linking the amount of adaptation and its cost to the level of mitigation action. The recognition of adaptation and mitigation as equally important is unique in the history of climate agreements. This article also makes specific reference to gender-responsive models and the valuation, ‘as appropriate’, of traditional knowledge, knowledge of indigenous peoples and ‘local knowledge systems’ with reference to the integration of such knowledge in relevant socioeconomic and environmental policies.

Article 8: This article arguably puts loss and damage on equal footing with mitigation and adaptation, which may be interpreted as recognition of the demands of small islands and other highly vulnerable countries to climate change; including through the Warsaw International Mechanism, on a cooperative and facilitative basis with respect to loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change. However, the omission of any liability or compensation requirements removes the possibility of climate reparation claims arising from developed countries’ responsibilities, given that historically they have contributed significantly more to atmospheric carbon accumulation than developing countries.

Article 9: This article states that ‘developed country parties shall provide financial resources to assist developing country parties with respect to both mitigation and adaptation in continuation of their existing obligations under the Convention’. It thereby reinforces that the developed countries collectively commit ‘to provide new and additional resources […] approaching USD 30 billion for the period 2010– 2012’ and ‘USD 100 billion dollars a year by 2020 to address the needs of developing countries’ (UNFCCC 2009, p. 7).

Article 13: This article recognises the importance of transparency to promote effective implementation in order ‘to provide a clear understanding of climate change action in light of the objective of the Convention as set out in its Article 2’. Transparency through monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV), has been interpreted as binding for all parties with respect to all elements contained in the Paris Agreement.

Article 14: This article introduces the concept of a ‘global stocktake’. Following on from Article 13, parties commit to providing comprehensive, facilitative and transparent periodic inventories to assess collective progress towards achieving the purpose of the Paris Agreement and its long-term goals. The COP also commits to taking its first global stocktake in 2023 and every 5 years thereafter. This is likely to be in recognition of the Intended Nationally Determined Contributions’ shortfall in terms of limiting global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels, given that, at best, they point towards a global average temperature increase of 2.7 °C if not 3 °C by 2100. This article implies that collective efforts will be assessed in 2018 to help update and enhance individual country plans to provide the basis for the first global stocktake in 2023.

Article 15: This article states that ‘a mechanism to facilitate implementation of and promote compliance with the provisions of this Agreement is hereby established’. Following paragraphs emphasize that the mechanism shall consist of an expert-based, facilitative committee and function transparently, non-adversarially and non-punitively with particular attention to respective national capabilities and circumstances of parties. It will serve as a meeting of the parties to the PA at its first session and will then report annually to the COP serving as the meeting of the parties to the PA.

Towards an Experimental Climate Governance

The long road towards finding a global response to climate change finally resulted in a momentous milestone in international politics, the Paris Agreement. Yet, several challenges await the effective implementation of the Agreement’s ambitious objectives. It is evident from the PA that the diplomats tried to reconcile the lack of ambition within the INDCs with the need to limit carbon emissions further to remain within a reasonable chance of limiting global average temperature rise to 2 °C. As the UNFCCC notes with concern the INDCs submitted to the UNFCCC are not sufficient to hold the increase in global average temperature to below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels, instead leading to a projected level of 55Gt of carbon emissions in 2030 although no more than 40Gt of carbon emissions may be released in 2030 to limit global average temperature rise to 2 °C. On a more positive note, the negotiations surrounding the (market and nonmarket) approaches to mitigation—which were among the last to be finalised on the last night of COP21 before the text was finally approved by the COP21 president, French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius—resulted in a text, which offers wide ranging possibilities. The origins of this text lie in a number of submissions prior to COP 21, including those of Brazil (November 2014); Japan (September 2015); AOSIS (December 2015); EU-Brazil (December 2015); LMDC (December 2015); and Panama (December 2015). The Brazilian submission of 10 November 2014 is of particular interest here because it introduces the concept of ‘Economic Instruments’ that features prominently in Article 6 of the PA: The Economic Mechanism shall be comprised of general guidelines related to an ETS and an enhanced Clean Development Mechanism (CDM+). (…) The new market mechanism (…) should be established under the agreement, incorporating the modalities, procedures and methodologies of the Clean Development Mechanism, to allow trading of CER among all parties.

Building upon Article 6, its history and the possibilities for its interpretation as a tool for the implementation of new, experimental climate governance regimes, opens a unique window of opportunity for a real, economically viable and socially acceptable low-carbon transformation.

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement as Foundation for the Mitigation Alliance

Although it has been generally hailed as a breakthrough in international climate change policy, several unsolved issues still surround the Paris Agreement. Misalignment between its ambitious objectives (the 2 °C/1.5 °C target) and its designated means of implementation (the Nationally Determined Contributions— NDCs) represents the biggest challenge. Parties are not required to strictly align their NDCs with the PA’s 2 °C/1.5 °C objectives as a result of the Common But Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities principle (CBDR-RC). Nevertheless, the PA includes a clause, represented by its Article 6, which offers a window of opportunity to overcome this impasse. Limited to parties that voluntarily collaborate for higher mitigation ambition, hence bypassing the possibility of vetoing that affected the history of climate negotiations, A6PA allows for experimentation with new models of climate governance capable of meeting all the PA’s objectives.

Unveiling Article 6

As with many other sections of the PA, Article 6 was not only the product of diplomacy and compromise but first and foremost the product of science. Understanding the features of the governance models proposed by A6PA first requires the identification of its scientific references. On the one hand, its climate change and sustainability aims—like the entire PA—follow the recommendations of the Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change(IPCC). On the other hand, its political and economic structure finds its origins in the climate clubs’ literature, as well as in the game theory framework. Many business leaders and government officials urge the use of carbon pricing as the most effective policy instrument in directly tackling emissions. Article 6 of the Agreement provides a foundation for international cooperation through markets, with the value of carbon pricing incentives noted in paragraph 137 of the decision text.

The creation of carbon pricing systems and the transfer of units between them can direct large scale financing towards the most effective mitigation activities whether sector level or project based. The broader the base for a given carbon price, the more efficiently it operates and the lower the overall cost of managing emissions to the economies within which it is operating. So, international links between markets can achieve even deeper cuts and assist the transfer of significant climate finance to help fund NDCs of interested developing economies.

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement provides the opportunity to expand the reach of carbon pricing to enable full implementation of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC). Its development should be guided by the fundamental principles of ensuring environmental integrity and avoiding double counting.

Article 6 has two key features:

1. It describes the use of internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMO). The concept of exchange of carbon units, either notional or real, should be an underpinning feature of any ITMO to ensure appropriate accounting.

2. It establishes a mechanism to contribute to the mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions, or an Emissions Mitigation Mechanism (EMM), and support sustainable development. The EMM, in conjunction with the ITMO, could be designed to promote carbon pricing. With the full implementation of the Paris Agreement, the EMM could offer a universal carbon allowance or credit for those countries that choose to use it, facilitating trade between NDCs (i.e. ITMO), providing registry facilities and therefore offering the prospect of carbon pricing in many economies. This in turn could channel additional investment. Therefore, IETA recommends a broad interpretation of Article 6.4 and having an open framework that will help governments account for emission reductions achieved.

While the Kyoto Protocol operated on an economy wide basis in a limited number of countries and at a relatively small scale in all others, the Paris Agreement must completely transcend this in order to realize the ambition embedded within it. Economy-wide action must become the model, both through large scale sectoral and project activity.

The creation of carbon pricing systems and the transfer of units between them can also direct large scale financing towards mitigation activities. During the first period of the Kyoto Protocol, the use of the Clean Development Mechanism, even at modest scale, directed tens of billions of dollars of finance to projects in emerging economies. Likewise, the voluntary carbon market has also directed significant additional dollars to similar projects, albeit often in other sectors such as forestry and agriculture.

Within this context sits the carbon trading or market-based provisions of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC)

All Parties to the PA are required to communicate NDCs. For all Parties, this represents a future emissions trajectory, typically 5 to 10 years. This is equally true for countries that have submitted a series of actions that comprise their NDC, as it is for countries that have specified a particular emissions target where a carbon emissions trajectory can be derived.

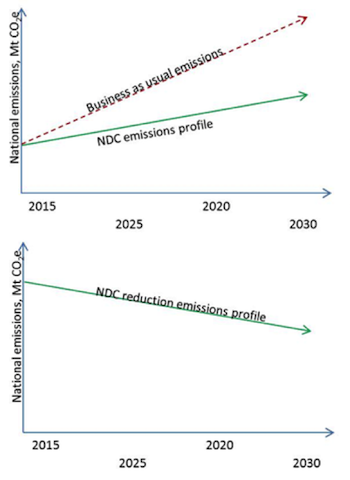

In the context of emission trajectories, there are three archetype NDCs;

Fixed Economy Wide Emissions Pathway (Type 1): This is an NDC based on a specific emissions target. For example, the economy is at 100 emission units in some reference year and has a trajectory that takes it to a new point of emissions in a future year. The total number of units between the two years represents a fixed emissions limit that should not be exceeded. There is a comprehensive national GHG inventory and international reporting system in place which tracks emissions and could incorporate carbon unit trade.

Examples of Type 1 NDCs include the European Union, the United States, Brazil and Japan.

Anticipated Economy Wide Emissions Pathway (Type 2): This is an NDC based on a desired emissions trajectory, which may be expressed as a deviation from business as usual, an emissions intensity at some future date, or simply a peaking year. For example, an economy may be expecting a certain rise in emissions over the forward period, but anticipates a different outcome subject to the full implementation of its NDC. There are two emission limits to deal with; the first is the limit related to the projected or business as usual rise in emissions over the forward period. The second is the limit associated with the anticipated or target outcome itself and can be converted into an absolute emissions limit over the period.

Examples of Type 2 NDCs include China, the Republic of Korea, Mexico, and Indonesia.

Other NDC Types (Type 3): There are a wide variety of NDCs based on a set of actions within the economy that gives rise to a notional emissions trajectory. The effort is focused on implementing the actions, such as energy efficiency projects, forest sequestration, or renewable energy deployment, rather than on managing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions. No emissions limit is immediately attributable to such an NDC, and therefore the opportunity for international trade of carbon units is more limited. However, if a sector within a Type 3 NDC operated against a baseline of some description, basic overall national GHG accounting could open it to trading opportunities.

Examples of Type 3 NDCs include Papua New Guinea, Uruguay, Samoa, and Bolivia.

Future NDC development (i.e. post 2020) should see a shift towards Type 1 and Type 2 structures.

Carbon trading between Type 1 NDCs is relatively straightforward, given the existence of registries, the likely implementation of cap-and-trade architecture in some part of the economy and the robust governance that these bring. While the Type 1 NDCs typically reflect single point-year targets, the trading systems would likely require annualized targets for each year of a compliance period to avoid double counting.

Carbon trading involving a Type 2 NDC requires additional consideration, in that models based on previously established international emissions trading architecture may not be appropriate. In particular, within a number of existing emissions trading systems established to date, the concept of crediting (a form of offset for emissions) has evolved.

In these systems a project can be defined which represents either a real (from a known XX tonnes to an expected YY tonnes) or notional (an expected YY tonnes, which is lower than a counterfactual XX tonnes) reduction in emissions outside the sectors not covered by the trading system itself. The difference “XX-YY” could then be realised as credits or offsets and be used to extend the supply of allowances within a trading system by effectively adding to the existing allowance pool. These units are typically awarded after an action is taken and a verification report is reviewed and approved by a regulator.

The transfer of these units from the project outside the trading system to the recipient inside the system has typically only impacted the emissions inventory of the latter. This construction has been possible because of the limited scope of climate action globally under the Kyoto Protocol; only certain countries and specific sectors have emission reduction goals, and therefore only these entities had a responsibility to directly manage and report on their emissions inventories, to the extent that they accounted for trade.

But the structure of the Paris Agreement and its overarching goal to eventually manage the entire global emissions inventory fundamentally changes this construction, as it involves all countries.

In the illustrations below are examples of two NDC constructions. The first is an NDC that proposes to shift the emissions profile from the Business as Usual (BAU) projection to a new, lower projection (Type 2). The projection may have a dependency, such as the availability of climate finance. A second country proposes an NDC on the basis of a quantifiable reduction goal (Type 1).

Under the Paris Agreement, the green ‘emissions profile’ lines should both be delivered. This means that reductions from the BAU line to the NDC line in a given Type 2 country cannot immediately be used as offsets elsewhere, which may have been the case previously under the Kyoto system. Rather, if emissions trading between these two systems dictates that projects are preferentially executed in the Type 2 NDC country, the transfer of units from that system must be accounted for such that the total emissions of the two entities does not exceed the total dictated by the green lines. A similar accounting structure existed under the Kyoto Protocol through Joint Implementation (JI), covering the implementation of a project in a country whose emissions were governed by an allocation of AAUs (Assigned amount units). Under that system, the host country of the project would effectively transfer AAUs to the recipient country, but this typically occurred through use of Emissions Reduction Units (ERU) under JI (Joint Implementation). The host country would be left with fewer AAUs and therefore a more stringent national target, but one that had nevertheless attracted external investment.

Article 6.4 – A mechanism to contribute to mitigation The second component part of Article 6 is the creation of a mechanism to contribute to the mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions, or an Emissions Mitigation Mechanism (EMM). Its core purpose could be defined so as to deliver an emissions reduction against some reference which is contained within the NDC, but also to ensure an overall reduction in global emissions while delivering sustainable development benefits.

In summary, the EMM of Article 6.4 could be designed to provide flexibility for countries seeking to implement carbon pricing mechanisms by offering the following;

• Quantify and deliver emission reductions (as an allowance type of unit) against an emissions reference level in a Party’s NDC;

• Provide a universal emission reduction credit or emissions allowance that can be transferred from one country to another as an ITMO;

• Encourage large-scale emissions mitigation activities as cost-effectively as possible;

• Undergo and follow oversight rules on the EMM set by the COP;

• Promote sustainable development through economic transition across all sectors of the economy emissions.

Human Rights and Climate Change

The United Nations has consistently insisted that people have environmental rights – protections from adverse environmental conditions, such as desertification. It should first be noted that the UN General Assembly, the Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights, the Human Rights Council, and the UN Environment Programme have long stressed the commitment that environmental rights are universal and that vulnerable people must have special environmental protections .As early as 2008, the Human Rights Council adopted resolutions highlighting the importance of protecting vulnerable people from adverse climatic events. On June 28, 2016, the United Nations Human Rights Council unanimously adopted a resolution on climate change that clarified and affirmed the rights of vulnerable persons to assistance and resources. It is important to highlight some of the provisions of this resolution since it not only affirms all of the rights included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights), but it also clarifies that development is a right, that environmental rights are universal, and that the rights of vulnerable people need special protection under the conditions of climate change. Moreover, it highlights that we strengthen and fortify human rights under the conditions of warming.

The 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change is relevant to human rights law, not for what it says about human rights— which is next to nothing—but for what it says about the need to address the risk of climate change taking global temperatures above 1.5 or 2 °C. The Agreement could work, or it could fail by a large margin, but those who want to influence the outcome can still do so. That includes the human rights community. Since climate change is plainly a threat to human rights, how should the UN human rights institutions respond? Should they use their existing powers of oversight to focus attention on how States parties implement (or fail to implement) commitments made in the Paris Agreement? Or should they recognize a right to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment? Either choice would represent a significant contribution to the debate on human rights and climate change, giving humanity as a whole a voice that at present is scarcely heard.

The NDCs will play a central role in the framework established by the Paris Agreement as they form the implementation plans through which each national government defines the level of its commitment and identifies how it will implement its obligations. To ensure that climate action is carried out at the national level in a manner that is coherent with existing obligations related to human rights and sustainable development, NDCs must be designed in a participatory manner and go beyond quantified targets and support actions to elaborate on how their implementation will contribute to respect and promote other international obligations.

First, the guidelines outlining the nature and scope of the NDCs should require parties to prepare their contributions in a manner that enables the full and effective participation by civil society, local communities, and indigenous peoples, as well as marginalized populations, women and youth, migrants, people with disabilities, other groups in vulnerable situations, and populations affected by climate response measures.

Second, parties should include information in their NDCs regarding how their commitments reflect the respect for and promotion of the principles reiterated in the preamble of the Paris Agreement. In particular, parties should be encouraged to provide information about how these principles have informed the determination of the ambition contained in the NDC and the selection of specific policy options.

The relationships between the SDGS and the Paris Agreement

To highlight the links between the SDGs and the Paris Agreement, we should analyze the excerpts from the Preamble and Article 2 of the Paris Agreement.

Number 1 (a) of Article 2 is clear: the aim is to limit the increase to 1.5 degrees above preindustrial levels.

In number 2, the term “differentiated responsibilities” highlights that rich countries have the responsibility to ensure that developing countries can meet their obligations to reduce emissions and develop clean energy technologies. This implicitly recognizes the historical legacies of colonialism and exploitation, and at the same time resonates with the SDGs. For example, SDG 17 highlights that richer countries assist developing countries. Note, too, the overlap between the SDGs and the Paris Agreement.

Goal 13 of the SDGs refers to climate change directly and 14 and 15 do so as well (respectively, ocean acidification and desertification). The Paris Agreement refers to “sustainable lifestyles,” “sustainable development,” “sustainable management of forests,” “sustainable environment,” and links sustainability with reduction of poverty, non market approaches to the economy, mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions, management of natural resources, and economic growth. Therefore, the goal of achieving zero emissions is inseparable from advancing and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

- United Nations Climate Change, ‘What is Paris Agreement?’ https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/what-is-the-paris-agreement

- IETA (2016), ‘A vision for the market provisions of the Paris Agreement’, May 2016 https://www.ieta.org/resources/UNFCCC/IETA_Article_6_Implementation_Paper_May2016.pdf

- Stua Michele (2017), From the Paris Agreement to a Low-Carbon Bretton Woods, Rationale for the Establishment of a Mitigation Alliance

- Judith Blau (2017), The Paris Agreement Climate Change, Solidarity, and Human Rights

- Alan Boyle (2018), Climate Change, the Paris Agreement and Human Rights

- Delivering on the Paris Promises: Combating Climate Change while Protecting Rights Recommendations for the Negotiations of the Paris Rule, https://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Delivering-On-Paris-Web.pdf

- United Nations, Paris Agreement (2015), https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf