INTRODUCTION

To the very beginning of business corporations, in the late 18th and beginning of 19th century, the corporate goal was to make sure that the business world would provide good service at a reasonable price – not to maximise investment returns. In the last decades of the 20th century, a broad consensus had emerged in the Anglo-Saxon business world that corporations should be governed according to the philosophy often called shareholder primacy (Stout, 2013). According to this theory, shareholders own the company and as a matter of fact, the main goal of the firm is to

maximize their value. Today this consensus is crumbling.

Indeed, the new debate on governance was quite recently given fresh impetus by the collapse of the US energy corporation Enron and on the end to corporate innocence (Branston and Tomlinson, 2002). The paper is then structured in three main parts: In the first part, I introduce the Enron’s

scandal and the reasons for the moral responsibility of the firm and its executives, questioning the shareholder’s inability to prevent managers in their corporation from pursuing dubious and illegal strategies towards the shareholders themselves and other stakeholders, as its employees, the energy crisis in California and the damages of the population in the region of Dabhol, India; In the second part, having discussed the Enron’s case, I question the new commitment of the firm towards the society and the evolution of the social contract between the two and I then explore the necessity to re-elaborate a corporate structure based on the normative Stakeholder theory. Consequently, I also discuss stakeholder management: Here stakeholders are to be intended as a political strategy for the organizational and managerial decision-making in order to respond and to adapt to the external environment’s requests and expectations; Eventually, I introduce the concept of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) as a model of multi-stakeholder and multi-fiduciary Approach. Enel represents a successful Italian example that has introduced CSR, sustainability and stakeholders among its goals.

1. Moral responsibility and the firm: The Enron Case

The Enron scandal given out in October 2001, showed how Enron Top officials abused their privileges and power and manipulated information to put their own interests above those of their employees and the public. It also failed to exercise proper oversight or shoulder responsibility for ethical failings that eventually led to the bankruptcy of this American energy company based in Houston, Texas, and the dissolution of Arthur Andersen, which was one of the five largest audit and accountancy partnerships in the world. The company’s failure in 2001 represents the biggest business bankruptcy ever while also spotlighting corporate America’s moral failings. It is a stark reminder of the implications of being seduced by charismatic leaders, or more specifically, those who sought excess at the expense of their communities and their employees (2013, as cited in Hosseini and Mahesh, 2015). The Enron scandal represents a major example not only of accounting fraud but also questions the moral responsibility of both the corporation and its top executives.

1.1 History of Rising and Failure

Enron was “a provider of products and services in natural gas, electricity, and communications to wholesale and retail costumers”, and had its roots in Omaha, Nebraska (Hosseini and Mahesh, 2016). In 1985, Houston Natural Gas merged with Inter North to form an energy company based in Houston, Texas. The company created the first nationwide natural gas pipeline system by integrating several pipeline systems. In 1986, the former chief executive officer (CEO) of Houston Natural Gas, Ken Lay, was named CEO and chairman of the fresh energy company. After one year, Enron Corporation in England opened its first overseas office: companies pursue the unregulated market by regulated pipeline businesses as a new strategy which was revealed to senior officials. Jeffrey Skilling joined the corporation in 1989 and launched Gas Bank, a program under which at fixed prices buyers of natural gas could lock in long-term supplies and corporations at the same time as oil and gas producers started to offer to finance. Skilling became then the CEO from December 2000 to August 2001.

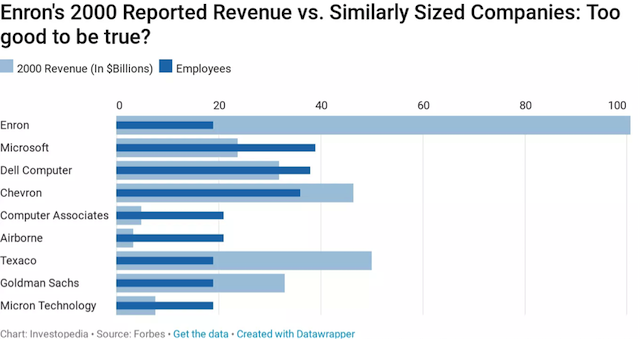

Throughout the late 1990s, Enron was almost universally considered one of the country’s most innovative companies, and it was often referred to as a starter of a “new business model”, a benchmark for the future energy and power industry (Gibney, 2005). Indeed, Enron’s annual revenues reached one hundred billion dollars in 2000, which was also reflecting the growing importance of trading. While the company continued to build power plants and operate gas lines, it was better known for its unique trading businesses (Li, 2010). Enron’s business expanded into several areas such as developing pipelines and a power plant, but all these expansions required large initial capital investments. As matter of fact, Enron raised a lot of debt funds from the market, and any other attempt to raise funds would affect Enron’s credit rating. Because the company did not make enough profits but still wanted to maintain its credit ranking at the investment rate in order to keep doing business, it began making partnerships and other special arrangements like ‘special purpose entity’ (SPE). These companies were used to keep Enron’s debts and losses away from its balance sheets, therefore allowing it to have a good credit rating and to be a safe financial asset to invest in. At the same time, Andersen, Enron’s auditing firm, did not fulfill its duties – which was to check that the company’s accounts were a fair reflection of what was really going on. But Andersen earned too much in fees for audit and consultants work from Enron Company.

Why did Enron go bankrupt?

• Lack of truthfulness by the management about the health of the company. The senior executives believed Enron had to be the best at everything it did, and they had to protect their reputations and their compensation as the most successful executives in the US. Maximizing the firm’s value through the rise of the stock price would have increased the corporation’s reputation and its leading position among its competitors. Showing the public the real balance-sheets would not have the same result. In fact, employees – who were told by the CEO that the stock price was about to rise – learned only during the investigation surrounding its bankruptcy that the CEO was at the time selling his stock.

• Conflicts of interest and a lack of independent oversight of management by Enron’s board of directors. In addition, even Enron’s compensation policies based on earnings growth and stock price may have pushed towards the executives’ risky decisions.

• The reputation of Arthur Andersen. The magnitude of the alleged accounting errors, combined with Andersen’s role as Enron’s auditor and the widespread media attention, provide a seemingly powerful setting to explore the impact of auditor reputation on client market prices around an audit failure.

• Mark to market and Special Purpose Entity (SPE): tools to commit accounting fraud. Mark to market: One of the skilling contributions was the introduction of the Mark to market accounting method, for which the company received official SEC approval in 1992. As a large public company, Enron was subject to external sources of governance, including market pressures, oversight by government regulators, and private entities as auditors, equity analysts, and credit rating agencies. Once a long-term contract is signed, the amount of which theoretically will sell on the futures market is reported on the current financial statement. Mark-to-market aims to provide a realistic appraisal of an institution’s or company’s current financial situation, and it is a legitimate and widely used practice. However, in some cases, the method can be manipulated, since MTM is not based on “actual” cost but on “fair value,” which is harder to pin down. Some believe MTM was the beginning of the end for Enron as it essentially permitted the organization to log estimated profits as actual profits (Segal, 2019). In order to keep appeasing investors, Enron traders were persuaded to forecast high future cash flows and low discount rates on the long-term contract with the company. The difference between the calculated net present value and the originally paid value was regarded as the profit of Enron. By purpose, the corporation was highly overvalued.

SPE: Fastow and others at Enron orchestrated a scheme to use off-balance-sheet special purpose vehicles (SPVs), also known as special purposes entities (SPEs), to hide its mountains of debt and toxic assets from investors and creditors. The primary aim of these SPVs was to hide accounting realities rather than operating results. The accounting rule allowed the company to exclude an SPE from its own financial statements if an independent party has control of the SPE and if it owns at least 3 percent of the SPE. In fact, Enron needed to hide its debt levels to avoid the lower of the investment-grade and that banks would recall for money back. Using the stock as collateral, the SPE, which was headed by the Chief Financial Officer (CFO), Fastow, borrowed large sums of money. Enron would transfer some of its rapidly rising stock to the SPV in exchange for cash or a note. This money was then used to balance its overvalued contracts. Thus, the SPE enabled Enron to convert loans and assets burdened with debt obligations into income. However, the debt and assets purchased by the SPE were not reported on Enron’s financial report. Shareholders were then misled that debt was decreasing and revenue was increasing.

In this scenario, Anderson played a fundamental role: as an auditor but also as a consultant to Enron, had to be responsible for both managers and shareholders since the provided accounting information has a direct influence on the economic benefits of both parties. Like the Prisoner’s dilemma game, the managers and the audit firm chose to betray the shareholders to maximize their self-interest.

2. From Shareholders to Stakeholders: The New Goal of the Firm

Through the example of the Enron scandal, the paper explained how a corporation is subject to certain moral duties and rules to follow, that can be judged moral responsible for its unethical actions and that its agents can be subject of punishment. However, in Enron, the stakeholder’s interests were not fulfilled as well as the shareholder’s ones. In other cases, even ensuring that the maximisation of shareholder’s wealth is achieved does not correspond to the protection of stakeholders; At the same time, their role is becoming much more important than having as a goal profit-making. For this reason, recognising that a corporation has to act within ethical and morally responsible behaviour is not enough to identify a new organizational and managerial structure of the firm. I shall then introduce the concept of stakeholder as both normative and strategic perspective.

2.1 Introduction to the notion of stakeholders and to the extended fiduciary duty theory

Opposed to the traditional (or better, of the last decades) belief of the shareholders’ value maximization I shall introduce the concept of stakeholders at the normative level.

We have seen that a shareholder is a person who owns an equity stock in the company and therefore holds an ownership stake in the company. Thus, it is an entity with a financial interest in the company’s profitability. If the company’s share price increases, the shareholder’s value increases, while if the company performs poorly, its value declines. Consequently, shareholders would prefer the company’s management to take actions that increase the share price and dividends, and that improve their financial positions. Also, shareholders would want the company to focus on expansion, acquisitions, mergers and other activities that increase the company’s overall financial health.

Traditionally, companies were only answerable to their shareholders. The idea was largely based on the theory of Milton Friedman (1970) – elaborated in an article of the New York Times Magazine entitles “The Social Responsibility of Business is to increase its Profits” – in which he affirms:

“There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception and fraud”.

On the other hand, a stakeholder is an interested party in the company’s performance for reasons other than capital appreciation. They can affect or be affected by the company’s policies and objectives. The broadest definition of the concept is found in the work of Freeman (1984) where “A stakeholder is by definition any individual or group of individuals that can influence or are influenced by the achievement of the organization’s objectives”. They can be either external or internal: Internal stakeholders have a direct relationship with the company through employment, ownership or investments. Some examples include employees, shareholders, and managers; External stakeholders are parties that do not have a direct relationship with the company, but they can be affected by its actions. Examples include suppliers, creditors, community and public groups. Overall, stakeholders would focus on longevity and better quality of the service (CFI, 2020). For examples, the employees may be interested in better salaries and wages; The suppliers may be interested in timely payments for goods delivered to the company as well as better rates for their products and services; The costumers will be interested in receiving better customer service as well as buying high quality products; The local community will be interested in topics as the safeguard of the environment and protection of human rights.

Without any doubt, the mantra of shareholder value maximization has been socially ingrained into the economic institution (Dawuda and Dery, 2016). However, different countries also take different views. In the “Anglo-Saxon” economies, the idea of maximizing the shareholder value is widely accepted as the chief financial goal of the firm. In other countries, workers’ interests are put forward much more strongly. For them, dividends should come first. In Germany, workers in large public companies have the right to elect up to half of the directors to the companies’ supervisory boards. As a result, they have a significant role in the governance of the firm and less attention is paid to the shareholders. In Japan, managers usually put the interests of employees and customers on a par with, or even ahead of, the interests of shareholders. For this point of view, job and environment security come first. However, as capital markets have become more global, companies in all countries face greater pressure to adopt wealth creation for shareholders as a primary goal. Some German companies, including Daimler and Deutsche Bank, have announced their primary goal as wealth creation for shareholders. In Japan there has also been some movement in this direction as the proportion of foreign ownership of corporations has significantly increased in recent times (Brealey, Myers and Allen, 2014).

At the same time, there has been spreading an increasing awareness of the impact that these entities have in our everyday life. Besides, actual corporate conduct in some cases is inconsistent with shareholder value maximization as the sole objective of the corporation. Specifically, the largest corporations’ impact on the society is becoming more and more predominant, especially after the spreading of the concept of sustainability and environmental protection. As the concentration of economic activity and power in a few corporations has resulted in a few companies having a large impact on the society and increasing separation of ownership and control, their role has been increasing in complexity (Serafeim, 2014). Nowadays not all corporations have the same role in society, and those that can have a greater impact, can be a function of a broader economic, social, and political context. A vicious circle can be identified: Not only the actions of the private sector and its impact in internal and external stakeholders have been changing its intrinsic role and structure, but the increasing corporate engagement on environmental and social goals has redefined the relation between business and society.

As a matter of fact, the stakeholder theory has been gaining more attention. The theory is based on the assumption to except the concept of fiduciary duty – from a mono-stakeholder perspective (where the sole relevant stakeholder is the owner of the firm) – to a multi-stakeholder one in which the firm owes fiduciary duties to all its stakeholders (the owners included). The multi-fiduciary approach views stakeholders as more than just individuals or groups who can wield economic or legal power. This view holds that the management has a fiduciary responsibility toward stakeholders just as it has this same responsibility toward shareholders. Hence, in order to promote some levels of ethical decision among the business decision-making actors, a more legal approach is required. Extended fiduciary duties are indeed necessary as:

1. Contracts are incomplete in the sense that some contingencies are unforeseen: Concrete and contingent provisions cannot be explicitly written or implicitly agreed with reference to such unforeseen events.

2. Parties may carry out specific investments that they can produce unforeseen events, or their effects can materialise under unforeseen states that cannot be ex ante described;

3. Under incomplete contracts parties’ behaviours are opportunistic: They would try for instance to renegotiate the contract in order to extract as much rent as possible from control over this relevant decision variable;

Extended fiduciary duties are necessary to prevent or at least mitigate the abuse of power of the management team and to favour a more ethical relationship. In fact, it is evident that if fiduciary duties attach only to ownership, thus those who have residual rights of control, the risk is an abuse of authority. The firm’s legitimacy deficit is remedied if the residual rights of control are accompanied by further fiduciary duties owed by the subjects not controlling the firm and at risk of the abuse of authority (Sacconi, as cited in Sacconi, Blair, Freeman and Vercelli, 2011). Those in a position of authority, in fact, can threaten the other stakeholders with exclusion from access to physical assets of the firm or appropriation of the surplus (Sacconi, 2004).

Given this explanation of the normative stakeholder theory, in the next paragraph it will be explained how the goal of the firms has to change as a consequence of their new relationship with the society and how the social contract between the two is evolving.

2.2.1 The new role of corporations in the society: balancing power with responsibility

The business and society relationship has generated many economic, social, ethical, and environmental challenges over the decades: Though the business system has served most market-based societies well and many progressive scholars see corporations as potential instruments for great good in society, this potential is often seen as underexploited because managers are severely constrained by their duties to shareholders (Maitland, as cited in Orts and Smith, 2017). Consequently, criticism of business and its practices has become commonplace. Beginning with the Enron scandal in the early 2000s, several major companies have been in the news because of their ethical violations. In the fall of 2008, a collapsing U.S. stock market and worldwide recession had a deeper and more far-reaching impact on the world economy and began to raise questions about the future of the business system as we have known it. Business and the capitalistic system have become the primary targets of the critics though flaws in the business-government relationship played a huge role in the controversy. By 2016, a number of different business scandals had surfaced and damaged the business – society – environment relationship further. These included the Volkswagen emissions scandal, admission by General Motors’ that it had schemed to conceal deadly safety defects in its ignition switches, revelations that Takata Corporation had been selling defective air bags, and disclosure that Toshiba had engaged in at least $1 billion in accounting irregularities (Carroll, Brown and Buchholtz, 2018).

Many different criticisms have been directed toward business over the years: Business is too big, it is too powerful, it pollutes the environment and exploits people for its own gain, it takes advantage of workers and consumers, it does not tell the truth, its’ executives are too highly paid, and so on. One of the most often repeated accusations about large businesses is that they have too much power. It is also claimed that they abuse this power. Whether or not business abuses its power or allows its use of power to become excessive, power should not be viewed in isolation from responsibility, and this power–responsibility relationship is the foundation for appeals for corporate social responsibility (CSR) that are at the heart of business and society discussions. Growing out of criticisms of business and unease regarding the power–responsibility imbalance has been an increased concern on the part of business for the stakeholder environment and a changed social contract.

2.2.2 The social contract

One way of thinking about the business–society relationship is through the concept of social contract, which is a set of reciprocal understandings and expectations. Social contract theory is an ancient philosophical idea that states that an individual’s ethical and political obligations relate to an agreement he/she has with every other individual within a society. The agreement can be written, as in the form of laws, or it can be a tacit agreement, an unspoken or unwritten agreement of social norms and customs. In business, social contract theory includes the obligations that businesses of all sizes owe to the communities in which they operate and to the world. If a firm is a team of participants with specific investments, then the metaphor of a bargaining cooperative game’s among multiple stakeholders can be applied. The bargaining cooperative game played by the stakeholders is typically one of mixed interests, in which cooperation and conflict coexist. The governance usually consists in two solutions: identifying a joint strategy of the stakeholders as the players in a cooperative game and ensuring ex post that each party complies with the agreement on the joint strategy. The social contract is articulated in two ways:

A. Laws and regulations. A framework – the ‘rules of the game’- in which the business can operate with its stakeholders.

B. Shared understanding. They evolve over time and they reflect mutual expectations regarding each other’s role, responsibilities and ethics.

The social contract between business and society has been changing over the years, and these changes have been a direct outgrowth of the increased importance of the social environment to many stakeholders. The social contract has been changing to reflect society’s expanded expectations of business, especially in the social, ethical, and sustainability realms. The new relationship between business and society and their social contract has led to a new importance given to stakeholder’s protections if the aim to pursue business ethics and sustainability. In the following section of the research I will investigate this new approach in order to understand what a firm must do to be socially responsible. Thus, not only the new ultimate goal of the firm must be expanded to those who have a stake in the company, but also that the stakeholder theory is might be strategic to respond to its new position within the society. This analysis will include what managers must do to be considered ethical; what responsibilities companies have to consumers, employees, shareholders, and communities in an age of economic uncertainty and globalization. And, throughout all this, an escalating mandate for sustainability has captured the attention of business leaders, critics, and public policymakers (Carroll, Brown and Buchholtz, 2018).

2.2 The stakeholder management: How ethics is integrated into managerial and organizational decision making

We already introduced the definition of the stakeholder theory in the business as a necessary normative tool to ensure long-term wealthy life of the corporation. However, as the stakeholder approach suggests that we redraw our picture of the firm, not only stakeholders must be integrated in the very purpose of the firm, but it is also a strategic management process that actively plots a new direction for the firm and considers how the firm can affect the environment as well as how the environment may affect the firm (Freeman and McVea, 2018). In this section, I will add to the previously describe stakeholder analysis, its management, which aspects are held together by the enterprise strategy – bearing in mind the ethics are still normative part of these processes.

2.2.1 The new corporate structure: identifying stakeholders

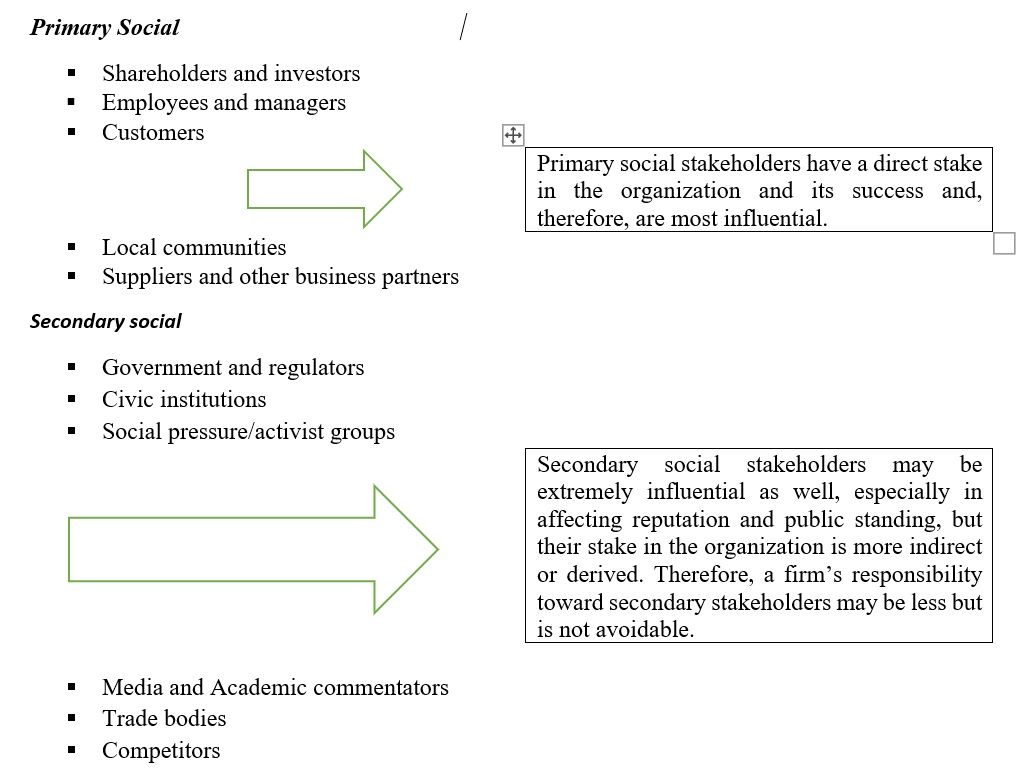

A significant area of interest to identify how to structure their management, has been the definition of legitimate stakeholders. In today’s hypercompetitive, global business environment, any individuals and groups may be business’s stakeholders. A useful way to categorize stakeholders is to think of them as primary and secondary as well as social and non-social.

Primary non-social

- Natural environment

- Future generations

- Non-human species

Secondary non-social

- Environmental interest group

- Animal welfare organisations

Nonetheless, all these categories can shift in their importance. For this reason, it is important to understand some quantitative criteria that might help managers to decide which stakeholder requires a major attention.

- Legitimacy. It refers to the validity or appropriateness of a stakeholder’s claim to a stake. Therefore, owners, employees, and customers represent a high degree of legitimacy due to their explicit, formal, and direct relationships with a company.

- Power. It is the ability or capacity of the stakeholder(s) to produce an effect—to get something done that otherwise may not be done. The stakeholder pressure can also be described as the ability and capacity of stakeholders to affect an organization by influencing its organizational decisions.

- Urgency. It refers to the degree to which the stakeholder’s claim on the business calls for the business’s immediate attention or response.

- Proximity – which is the spatial distance between the organization and its stakeholders.

All these criteria develop what they refer to as ‘the principle of who and what really counts.’ This line of research is particularly relevant in areas such as the environment and the grassroots of political activism (Freeman and McVea, 2018).

2.2.3 External and Internal Stakeholder Issues

In short, stakeholders can be approached both as a normative tool and as a corporate strategy to better respond to what the external environment requires. The stakeholder strategy is based on the view that companies and society are interdependent and so, stakeholders can influence on corporate decision and vice versa. At the same time, a company’s relationship-building strategy is seen as being inextricably linked to its mission, values and goals (Svendsen, 2010). However, the normative and strategic/political approaches of the stakeholders, may create some tensions in its definition and to which extend different subjects can be included in that category. In fact, from a strategic point of view, every actor with a potential influence or potentially influenced by the company can be defined as stakeholder. Thus, even the environment or the community in a broader sense can be identified as a possible stakeholder. I now shall introduce how, and which policies are needed to ensure external and internal stakeholder protection. A stronger ethical environment leads to better interactions with those inside and outside the organizations, meaning with all the stakeholders (Lampton and Curtis, 2019).

- INTERNAL STAKEHOLDERS: employees’ treatment and rights

Employees are essential to the creation of firm value and the financial success it provides, and so companies have a moral responsibility to create value for employees in their workplace experience and lives. Even though employees and workplace issues are complex and challenging, are anyway vital to effective stakeholder management. Three major themes or trends characterize the modern relationship between employees and their employers: the evolution of the social contract, the practice of employee engagement, and the expansion of employee rights.

- We have already discussed how the social contract between society and the business has been changing through the years because of the actual society’s expectations towards businesses: This has been reflecting in the employee – employer relationship. The workforce of today is more mobile, less loyal, and more diverse. Employees have come to know that their jobs are vulnerable, and so they have come to view themselves as free agents, bearing sole responsibility for their own careers. Nowadays, employees seldom look for a lifetime employment, but rather they seek competitive pay and benefits while also being part of a meaningful job. The new social contract represents an adaptation to the changing world of work and changing business circumstances but it also means the employers will have to invest more in employee engagement programs that foster loyalty and dedication as the employees expectations of fair treatment will also continue to rise.

- Companies that support employee engagement through mentoring programs, career development training, and annual employee surveys that result in actions have notable key outcomes. Employee engagement is a concept that is central to most business’s employee stakeholder management. It is particularly important as businesses deal with an increasingly distal workforce while still trying to instil a sense of identity with the organization that might inspire loyalty and commitment.

- Private corporations historically and traditionally have not had to recognize employee rights to the same degree of the public sector because society honoured the corporation’s private property rights. However, some social and ethical issues have become important to employee stakeholders in recent years, and rights to privacy, safety, and a healthy work environment are more often bought into discussion. Technological developments have made surveillance simpler and less expensive in public places as well as in the workplace. Besides, having increased the monitoring efficiency, the circumstances for workplace surveillance have also created challenges around privacy rights. Besides, as the world changes, so do the threats to worker health and safety. Unexpected or undetected threats to workers’ health and safety are certain to occur and will represent new challenges for managers. Socially responsible companies will strive to move beyond what is being required by law and to do what is right and fair for their employee stakeholders (Carroll, Brown and Buchholtz, 2018).

2. EXTERNAL STAKEHOLDERS

- Local community and public policy. When we think of business and its local community stakeholders, two major kinds of relationships come to mind: One is the positive contribution business can make to the community; the other one business can also cause harm to community stakeholders. Considering the latter, when a business decides to close down, downsize, or close a plant or branch, the loss of jobs represents the most direct and significant detrimental impact on the community stakeholders—including employees, local government, other businesses, and the general citizenry. At the same time, making profits and addressing social concerns are not mutually exclusive endeavours and thus, business can also make substantial contributions to the communities they serve. One of the most pervasive examples of business involvement in communities is a volunteer program and Corporate philanthropy, which is also called “business giving of financial resources by the business”. However, there can be a dark side to corporate philanthropy, as companies like Enron have demonstrated. Enron conducted a very generous corporate giving program, and this tended to make some people reluctant to examine the company’s business practices too closely (Kennedy, 2020). Besides, the community can be also intended in more general terms, extending the concept of community to the whole society and the public sector. In fact, business influences the Government and Public Policy. As it is also assuming further influence towards the whole society, the public sector has found itself forced to operate considering the actions of the private sector. Besides, the Government can be also influenced by corporate political activity. Traditionally, there are two mechanisms of corporate political activity: lobbying – the process of influencing public officials to promote or secure the passage or defeat of legislation – and political spending. At the same time, Government’s interest, or stake, in business is broad and multifaceted, and its power is derived from its legal and moral right to represent the public in its dealings with business. Government establishes the rules of the game for business and business has the responsibility of obeying the laws of the land and of being ethical in its responses to government expectations and mandates. Government is a major employer, purchaser, subsidizer, competitor, financier, and persuade: All these roles permit government to affect business significantly. Nonetheless, we have to underline a fundamental difference between local community and the government: The first is a stakeholder in terms of normative perspective while the second as a company’s political strategy in broader terms and though it is not to be included among the purpose of the firm.

- Consumers. Consumers’ protection can be succeeded through the protection of four fundamental rights: right to be safe from dangerous products, rights to be informed properly about the product through advertising, right to choose among competitors and right to be heard regarding their desires and complaints. Wrongful advertising behavior can be either corrected through a regulatory approach and use of penalties coming from the Government or either through self-regulation by the business itself. Besides, the product offered to the public need to be safe and of quality.

- The Natural Environment. The Brundtland Commission defined sustainable business as “business that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. Natural environment as becoming a major societal issue as business’ activities can have great impact on climate change, energy, water, biodiversity and land use, air pollution, deforestation, ocean and fisheries. Besides, other groups as NGOs or green consumers might have an interest stake in the company. Meanwhile, the pressures on the environment come from many directions. Climate change is more and more urgent and world population is projected to continue to grow, creating greater demands on food and fuel resources. Therefore, the business has no longer the luxury to decide whether respond to these urgencies. A company’s environmental responsibility derives from how a product is sourced, manufactured, and moved to market, but it’s also affected by what the company does at headquarters and how it works with its contractors (Consumer Dummies, 2020).

2.2.2 The managerial leadership towards ethical and sustainable business

We have seen that “ethics are ethics” regardless of whether they are applied at the personal, managerial, or organizational level. In many respects this is true. However, each level of application also introduces distinct challenges. The persona ethical dilemmas – which include situations we face in our personal lives that are generally outside the context of our employment but may have implications for our jobs – are indeed very different from the ones that managers or employees encounter. Managerial and organizational-level issues carry consequences for an individual’s status in the organization, for the company’s reputation and success in the community, and for the kind of ethical environment or culture that will prevail on a day-to-day basis at the office. A third level at which a manager or an organization might experience business ethics issues is the industry or profession level. The industry might be stock brokerage, real estate, insurance, manufactured homes, financial services, telemarketing, electronics, or a host of others. Related to the industry might be the profession, of which an individual is a member—accounting, engineering, pharmacy, medicine, journalism, or law. An excellent example of an industry-wide ethical problem occurred during the build up to the Wall Street financial scandals and market collapse in 2008. The mortgage-lending industry became enthralled with subprime lending. The industry became disreputable for its NINJA loans—loans to people with No Income, No Job, no Assets. For the sake of keeping up with the whirlwind competition, firms were granting loans just to keep up competitors and to collect commissions. This practice contributed significantly to the worldwide recession. At the societal and global levels, it becomes very difficult for the individual manager to have a direct effect on business ethics. However, managers acting in concert through their companies and industries and professional associations can certainly bring about high standards and constructive changes (Carroll, Brown and Buchholtz, 2018).

Therefore, managers of big corporations have great potential to affect our society and detained a great responsibility. Ethical leaders must stress the primacy of integrity and morality as vital components of the organization’s culture: Ethics is more about leadership than about programs. The manager has to follow the following features to ensure an ethical leadership within the business:

- Effective communication of ethical messages: It included written, verbal and nonverbal communication. Communications should be driven by the principles of candour, fidelity and confidentiality.

- Use of ethics and compliance programs along with officers to lead them in their initiatives and responsibilities. These typically includes features of written standards of ethical standards, mechanisms to seek ethical advice or information, evaluation performance of ethical conduct and so on.

- Setting realistic objectives or goals.

- Decision making is at the heart of the management process. Ethical decision making is not a simple process but rather a multifaceted one that is complicated by multiple alternatives, mixed outcomes, uncertain and extended consequences, and personal implications.

- Corporate transparency refers to a quality, characteristic, or state in which activities, processes, practices, and decisions that take place in companies become open or visible to the outside world

In short, the moral manager shall include being a role model to subordinates, constantly communicating the ethical standards and using reward and punishment to promote ethical behaviour within the subordinates. Northouse (2015, as cited in Tushar, 2017) has cited the five principles of ethical leadership which might influence individual to be ethical leaders who could be used as a role model.

- Respect others. According to the philosopher Immanuel Kant, it is our duty to treat others with respect all the time and as a leader, it also includes listening to his subordinates and the community.

- Serve others. The leader’s ethical responsibility is to serve others in order to serve the ‘greater good’.

- Demonstrate Justice and fairness. As we always have a limit on goods and resources, and there is often competition for those, the leaders play an important role in here to distribute and reward or punishments.

- Display honesty. The duty of being honest comes with the role of becoming a leader (Gilbert, 2016). In a business some example could be to do not promise what you cannot deliver or to not account for accountability.

- Build a community. A leader drives a group of individuals to achieve a common good for all.

The ethical role of a business leader has been taken into discussion in the last decades as the problem of environmental protection has risen. If the population is doubling every half a century, natural resources are not growing at all. Corporations are not only demanding ethical but even sustainable.

Thus, the sustainable organisation requires all the three legs above showed to properly functions. All the legs are needed, and they require the same amount of attention. Hence, a parallel leg, the stable floor of ethics, would be used to put the same attention to all the three pillars and it will serve to sustain the sustainable organization. As these organizations have a major responsibility in the sustainable development of the society, a strong and positive organizational culture represents an important prerequisite for sustainability of businesses.

3. The new firm: A balance between a corporate social responsibility and profitability

Having established that a corporation and its decision-making can be retained moral responsible for its decisions and what a firm must do in order to be socially responsible and respond to what the society has been requesting to act, a question come naturally: What is a corporation?

Thus, for ethicists the corporation is a moral agent; for economists it is a set of relationships designed to optimize efficiency; for social scientists it is a social arrangement with its own culture, both like and unlike families and civil societies (Williams, 2008). Is a corporation a legal entity only or rather, something more?

3.1 Corporate social responsibility as a model of multi-stakeholder governance: The relationships between ethics and rules

Whenever one talks about business ethics, both CSR and stakeholder theory come as two major concepts. However, there has been little clarity so far in what relation the two theories stand to each other. Both incorporate societal interests into business operations. Nonetheless, in the stakeholder theory, society is very important but only one part among other corporate social responsibilities, while CSR priorities the societal aspect over the others rather over the other business responsibilities. Besides, although the composition of stakeholders depends on the company’s industry and business model, the stakeholder theory tends to center its attention within a local community where the company operates and surrounding society, CSR tends to extend social orientation of the company much further. Although these differences, the stakeholder theory can be a useful tool to provide guidance on how the company should operate overall and all the company’s responsibilities to stakeholders could be denoted under the term corporate responsibilities. Furthermore, creating value for communities (CSR), does not create tension in value creation for other stakeholders (Freeman and Dmytriyev, 2017).

In fact, one convincing and implementable model of multi-stakeholder and multi-fiduciary corporate governance is CSR. Before describing what incentives and individual motivations can support it or whether a legal enforcement is required or not, and whether it may rest on self-enforceability, I will introduce first the definition of the model.

The EU Commission defines CSR as ‘actions by companies over and above their legal obligations towards society and the environment’ (2011). This definition explicitly includes the interests of stakeholders other than shareholders. It is indeed a strategic management that sets corporate standards of conduct at a higher level than mandatory legal constrains and it is also a governance of transactions between a firm and its stakeholders. It is indeed a governance that allows to reduce transaction costs and negative externalities by establishing rights and obligations. Therefore, Sacconi (2004) introduces the following definition of CSR:

“a model of extended corporate governance whereby who runs a firm (entrepreneurs, directors, managers) have responsibilities that range from fulfilment of their fiduciary duties towards the owners to fulfilment of analogous fiduciary duties towards all the firm’s stakeholders”.

Regarding the matter of implementation, some critiques oppose to business ethics as the basis for introducing forms of ethical and social self-regulation by firms. They invoke stronger regulations and imposition of hard law in order to oblige corporate actors to comply with even the minimal requirement of avoiding conflicts of interest. Without any doubt, the relationship between ethics and legal rules is a complex one. In fact, the definition of ethics – defined as the set of social norms commonly accepted based on agreements and conventions – is opposed to the one of imposing binding rules. From the perspective point of view, ethics precede the law, in the sense that an enduring legal order always rests upon an “overlapping consensus” on constitutional ethical principles (Rawls, 1993, as cited in Sacconi, 2004). Besides, ethics proceed together with the law, which leads with the spontaneous acceptance of the authority of the law and of the legitimate constitutional order; Finally, ethics go beyond the law. It regards to all the matters that cannot be protected specific rules but just by general principles or standards agreed by the parties concerned, or by private orders established by intermediate groups in society.

The idea is that the implementation of the normative model of multi-stakeholder corporate governance may rest largely on voluntary self-regulatory norms deliberated by companies. Effective CSR self-regulation is a viable option only within an institutional and legal environment that does not obstruct it, but as soon as the firm’s objective-function laws define the only goal the shareholders’ value maximization, would prevent the board from deciding to balance stakeholders‘ interests according to the social contract view. As CSR requires sustained stakeholder engagement, this collective approach means that corporate governance cannot just be about a fixed set of rules to be applied and enforced. Further, corporate governance laws can have better effects and outcomes if they can communicate, facilitate, and entrench effective and efficient governance without coercing (Tan, 2013). Most importantly, as we have seen that contracts are incomplete, responsibility intervenes as a remedy to contractual gaps by introducing internal restraints within the very exercise of legitimate authority over non-controlling stakeholders by owners and management. The self-regulation mechanism to implement CSR can be obtain through different approaches:

- Discretionary approach: self- regulation without specific rules. It is an enlightened self-interest which consists in an endogenous force able to induce self-discipline because it induces to account for personal interest into the long run. On this view, self-regulation is nothing other than self-discipline whereby the firm does not behave in a manner such to abuse the trust that stakeholders have placed in it.

- The reputation mechanism: It arises from the recognition of the firm of the importance of safeguarding and enhancing its reputation, which depends on non-abuse of the stakeholders. However, the main reason for weak self-regulation fails is the cognitive fragility of reputation.

The logic of the management of CSR that the firm’s strategic behaviour must conform to in a context of incomplete information in order that reputation effects are reactivated (Sacconi, 2004).

The principles must be general and abstract, so that their application does not require a detailed description of the situation;

Definition of the principles allows identification of areas of potential opportunism where interactions between stakeholders and firm put those principles at risk. precautionary rules of behaviour can be established which assure the relevant stakeholder that a form of opportunism has been avoided;

Principles and precautionary rules of behaviour must be communicated, given that reputation depends on them. Thus, communication and dialogue with stakeholders is essential.

3.2 CSR and financial performance relationship

A vital issue in corporate governance and management is the influence of CSR on companies’ performance, especially corporate financial performance (CFP). The conventional view holds that CSR is costly since being socially responsible incurs additional expenses. In fact, socially responsible actions as investments in pollution reduction or employee benefit packages, are costly. According to the traditional view, these expenses deteriorate the profitability of the firm. However, flowing the stakeholder theory of the firm, the dissatisfaction of any stakeholder group can potentially affect economic rents and even compromise a company’s future: CSR is therefore a prerequisite for protecting the bottom line and boosting shareholder value. If managed properly, CSR will not only improve the satisfaction of these stakeholders but also lead to improved financial performance. For example, satisfied employees will be more motivated to perform effectively, satisfied customers will be more willing to make repeat purchases and recommend the products to others, satisfied suppliers will provide discounts (Galant and Gadez 2016).

The evidence enquiry has been showed through the measurement of CFP and CSR, although it has been demonstrated to be problematic. The difficulty come from the way the two dimensions can be operationalised and measured. CFP is typically measured with accounting-based or market-based indicators with profitability ratios retrieved from financial statements that are relatively standardised and readily available. However, the first measurement relies just on historical data, while the second one gives data only to listed firms, leading to systematic errors.

The measurement of CSR is even more complex. The first challenge is the lack of consensus concerning operationalisation of the CSR concept; Secondly, regarding the measurement, information concerning this concept is mostly non-financial and there is little, if any, reporting standardisation; Finally, the last problems regards disclosure as CSR reporting in many jurisdictions is not mandatory. Due to the lack of consensus and complexity of the concept, it is not surprising that many different approaches have been used in the literature to measure CSR:

- Reputation indices by specialised rating agencies. Typically, they acknowledge the multidimensional nature of CSR. Most used index for measuring CSR is MSCI KLD due to its comprehensive and prominent data on stakeholder management. Some other authors claim that the Fortune index is most comprehensive and comparable, as it is included not only social responsibility but even other variables as the use of corporate assets, innovation, global competitiveness and so on. Another index is the so called Vigeo, which is commonly used when appraising European Countries where other indices are often not available. These indices are though characterised by some weaknesses: They are compiled by private firms that have their own agenda and not necessarily rely on scientific research; Plus, these rating agencies’ coverage is limited in terms of geography or number of firms rated.

- Content analysis of corporate communication. It usually consists into determining the construct of interest and codifying qualitative information to derive quantitative scales. The key advantage for the researcher is flexibility. Indeed, a researcher can specify CSR dimension of interest, collect data according to those dimensions and interpret and code data numerically for further use in statistical analyses. However, using this method the researcher subjectivity is highly embedded in all these stages of the research process.

- Questionnaire – based surveys. This method is used whenever a company is not rated by the rating agencies or corporate reports are unavailable or insufficient for a meaningful content analysis. Hence, the researches send questionnaire to respondents or interviewing them. Like the content analysis, this method provides great flexibility for the researcher but nonetheless, it can be subject of response bias. First of all, more responsible firms are typically more open to respond to these surveys. Besides, firms might be more likely to answer with desirable answers. One possible answer to this limit may be to open these interviews to stakeholders as well.

- One dimensional measure: It means focusing on just one aspect of CSR. Using this method, it easy to collect data and compare them with similar firms. Even though it might seem easier and more immediate method, it is important to remember that CSR – by definition – is multidimensional.

In short, there is not a perfect measure for both the identities. The empirical literatures fail to provide evidence of the possible influence of CSR on CFP showing that there is not a significant relationship between socially responsible activities and financial performance. But as we assumed that CSR as a normative multi-stakeholder corporate governance, the question is not whether CSR can positively effect the goal of financial beneficiaries; Rather, the question might be, as both the dimensions are complementary goals of the firm, how they can coexist successfully without undermining one to another. An important example is the Italian case of Enel, which has elaborated a CSR structure based on the its relationship with its stakeholders. Besides it has increased value and synergy with the external world, promising to fulfil the United Nations Sdgs. Indeed, while not undermining its financial performance, it committed to the Sdgs number 13 – reducing Co2 emissions and in 2018 the specific emissions were equal to 0,369 kg/kWheq – and 4,7,8, 9 and 11 – favouring the community access to education, energy and occupation and investing in resilient infrastructure, leading to sustainable communities and cities (standard ethics, 2019). The main Enel policies include:

- Besides the Committee for green bond emissions and management, Enel was one of the first organizations worldwide in 2018 to formalize the establishment of a permanent structure dealing with sustainable finance issues. This structure includes the “Finance-Capital Markets”, “Investor Relations” and “Innovability – Sustainability Planning and Performance Management” units, guaranteeing an approach that is integrated, inclusive and multi-disciplinary.

- Identifying and updating the list of the relevant categories of stakeholders; evaluating and weighting the different categories according to the parameters of dependence, influence and tension; engaging stakeholders as appropriate according to the communication channels.

Hence, Enel commitments include both sustainable finance in order to mitigate its action on the environment and enhance sustainable development and the understanding of stakeholders’ expectations as one of the crucial phases of the assessment (Enel, 2018). Hence Enel is succeeding in undertaking normative stakeholder and CSR models without undermining the more traditional goal of “making money”.

Conclusion

The Enron case is an important example that shows that a firm can be moral responsible for its unethical actions if they are demonstrated to causal, intentional and aware. The goal of the firm is not only to be a profit-making machine but, as ethical and moral agent, their duties towards stakeholders must be involved among its purposes. Enron also demonstrates that the shareholder supremacy might have a negative impact on stakeholders but also on the corporate wealthy life expectancy. Shareholder value-increasing strategies that are profitable for one shareholder in one period of time can be bad news for shareholders collectively over a longer period of time (Stout, 2013). Besides, shareholders as a class want companies to be able to treat their stakeholders well, because this encourages employee and customer loyalty.

Nearly 200 chief executives, including the leaders of Apple, Pepsi and Walmart, redefined the role of business in society — and how companies are perceived by an increasingly sceptical public. Given the potential impact of corporate’ actions, the public demands exceed to the protection of the environment by embracing sustainable practices across the businesses and to foster diversity and inclusion, dignity and respect. Klaus Schwab, the chairman of the World Economic Forum affirmed in an interview that “The threshold has moved substantially for what people expect from a company. It’s more than just producing profits for the shareholders.” (as cited in Gelles and Yaffe-Bellany, 2019). Indeed, many are and will be the firms that decide to introduce CSR as a corporate goal complementary to the financial performance. In short, the paper does not want to show that the implementation of CSR will ensure further earnings but rather, as the correlation is still uncertain and a standardisation does not exist, the two dimensions must coexist as both part of the goal of the new firm. The case of Enel Group is a current example of how a successful self-regulated business aim to be socially responsible for itself, the stakeholders and to the more general public and environment (CSR).

- Abun, D. (2015). “Corporate Moral Responsibility: Who is taking the blame”.

- Ethical issues and arguments. Web accessed from: http://dameanusabun.blogspot.com/2015/03/corporate-moral-responsibility-who-is.html.

- Branston, R., Cowling, K. and Sugden R. (2002). “Corporate Governance and the Public Interest”. Research Gate. Web accessed from: file:///C:/Users/marti/Downloads/Corporate_Governance_And_The_Public_Interest.pdf.

- Brealey, R., Myers, S. and Allen, F. (2014). “Governance and Corporate Control Around the World”. Principles of Corporate Finance. (New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin). 860-879.

- Carroll, A., Brown, J. and Buchholtz, A. (2018). “Employee Stakeholders: Privacy, Safety and Health”. Business & Society. (Boston: Cengage learning). 551-579.

- Carroll, A., Brown, J. and Buchholtz, A. (2018). “Managerial and Organizational Ethics”. Business & Society. (Boston: Cengage learning). 224-271.

- Carroll, A., Brown, J. and Buchholtz, A. (2018). “The Business and the Society Relationship”. Business & Society. (Boston: Cengage learning). 1-29.

- CFI (2020). “Stakeholder vs Shareholder”. Web accessed from: https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/finance/stakeholder-vs-shareholder/.

- Consumer Dummies. (2020). “Socially Responsible Investing: The Balance of Shareholder and Stakeholder Needs”. Web accessed from: https://www.dummies.com/personal-finance/investing/socially-responsible-investing-the-balance-of-shareholder-and-stakeholder-needs/.

- Dawuda, A. and Dery, L. (2016). “Examination of the moral rights of Stockholders and Stakeholders on the corporation”. Research Gate. Web accessed from: file:///C:/Users/marti/Downloads/PUBLICATION2559-RESEARCHJOURNALI%20(1).pdf.

- Enel. (2018). Sustainability Report. Web accessed from: https://www.enel.com/content/dam/enel-com/governance_pdf/reports/annual-financial-report/2018/sustainability-report-2018.pdf.

- Freeman, E. and McVea, J. (2001). “A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management”. Research Gate. Web accessed from: file:///C:/Users/marti/Downloads/A_Stakeholder_Approach_to_Strategic_Management.pdf.

- Freeman, E., Phillips, R. and Sisodia, R. (2018). “Tensions in Stakeholder Theory”. Business and Society. Web accessed from: file:///C:/Users/marti/Downloads/FreemanPhillipsSisodia2019BSTensions.pdf.

- Freeman, E. and Dmytriyev, S. (2017). “Corporate Social Responsibility and Stakeholder Theory: Learning From Each Other”. Symphonya, Emerging Issues in Management. Web accessed from: http://symphonya.unicusano.it/article/viewFile/2017.1.02freeman.dmytriyev/11574.

- Friedman, M. (1970). “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits”. The New York Times Magazine. Web accessed from: http://umich.edu/~thecore/doc/Friedman.pdf.

- Galant, A. and Cadez, S. (2017). “Corporate social responsibility and financial performance relationship: a review of measurement approaches”. Taylor and Francis Online. Web accessed from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1331677X.2017.1313122?src=recsys.

- Gelless, D. and Yaffe-Bellany, D. (2019). “Shareholder Value is no Longer Everything, Top CEOs Say”. The New York Times. Web accessed from: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/19/business/business-roundtable-ceos-corporations.html.

- Husseini, S. and Mahesh, R. (2016). “The Lesson from Enron case – Moral and Managerial Responsibilities”. International Journal of Current Research. Web accessed from: file:///C:/Users/marti/Downloads/168792.pdf.

- Lampton, J. and Curtis, C. (2017). “Strong Ethics Benefits all Stakeholders”. Strategic Finance. Web accessed from: https://sfmagazine.com/post-entry/february-2019-strong-ethics-benefits-all-stakeholders/.

- Landau, P. (2019). “Stakeholder vs. Shareholder: How They’re Different & Why It Matters”. Project manager. Web accessed from: https://www.projectmanager.com/blog/stakeholder-vs-shareholder.

- Langtry, B. (1994). “Stakeholders and the Moral Responsibility of the Business”. Business ethics quarterly. Web accessed from: file:///C:/Users/marti/Downloads/StakeholderTheory1994.pdf.

- Li, Y. (2010). “The Case Analysis of the Scandal of Enron”. International Journal of business and management. Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education. Web accessed from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0d3f/5648977c18f7fef842227fd43e4298c2c4dc.pdf.

- Orts, E. and Smith, C. (2017). “How insiders Abuse the Idea of Corporate Personality”. The Moral Responsibility of Firms. Maitland, I. (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Power technology. (2020). “Dabhol Power Plant, Ratnagiri District, Maharashtra, India”. Web accessed from: https://www.power-technology.com/projects/dabhol-combined-cycle-power-plant-maharashtra-india/.

- Roy, S. (2002). “India: Enron’s Debacle at Dabhol”. Corpwatch. Published by

- Pacific News Service. Web accessed from: https://corpwatch.org/article/india-enrons-debacle-dabhol.

- Sacconi, L., Blair, M. and Freeman, E. (2011). “A Rawlsian View of CSR and the Game Theory of its Implementation (Part I): The Multi-Stakeholder Model of Corporate Governance”. Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Governance. Sacconi, L. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan). 157-193.

- Sacconi, L. (2004). “Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) as a model of ‘extended’ corporate governance. An explanation based on the economic theories of Social Contract, Reputation and Reciprocal Conformism”. Liuc Papers n. 142. Web accessed from: file:///C:/Users/marti/Downloads/SSRN-id514522.pdf.

- Sacconi, L. (2008). “CSR as a contraction model of multi-stakeholer corporate corporate governance and the game-theory of its implementation”. Web accessed from: file:///C:/Users/marti/Downloads/SSRN-id1163704.pdf.

- lverstein, K. (2013). “Enron, Ethics and today’s Corporate Values”. Forbes. Web accessed from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/kensilverstein/2013/05/14/enron-ethics-and-todays-corporate-values/#7b201a1c5ab8.

- Stout, L. (2013). “The Shareholder Value Myth”. European Financial Review. Web accessed from: file:///C:/Users/marti/Downloads/SSRN-id2277141.pdf.

- Tan, E. (2013). “Corporate social responsibility as corporate soft law: Mainstreaming ethical and responsible conduct in corporate governance”. Singapore Law Review. Web accessed from: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4345&context=sol_research.

- Tushar, H. (2017). “The Role of Ethical leadership in Developing Sustainable Organization”. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science. Wb accessed from: file:///C:/Users/marti/Downloads/TheRoleofEthicalLeadershipinDevelopingSustainable.pdf.

- Williams, O. (2008). “The Purpose of the Corporation”. Peace through Commerce: Responsible Corporate Citizenship and the Ideals of the United Nations Global Compact. Smurthwaite, M. (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press).